| Colombia: el riesgo es que te quieras quedar sin un hermano | Colombia: the risk is that you want to be left without a brother |

| Aventura, Florida, 31 de diciembre del 2007 – 1º de Enero del 2008. Me terminé de tomar la champaña Veuve Clicqot de todo el mundo, porque en mi familia “nadie toma”. Ya pasada la media noche, al lado del mar, me acerqué a mi hermano Diego y le dije que yo soy todo lo que soy gracias a él, y que lo adoraba. Se le aguaron los ojos. A mí también. Y me dijo que me quería muchísimo y que estaba muy orgulloso de mí. Nos abrazamos muy fuerte. | Aventura, Florida, December 31st 2007 - January 1st 2008. I finished everybody's Veuve Clicquot champagne because in my family "nobody drinks". After midnight, with the view of the sea, I told my brother Diego that I am everything I am thanks to him and that I adored him. He got some tears in his eyes. Me too. He told me that he loved me a bunch and that he was very proud of me. We hugged each other very strongly. |

| |

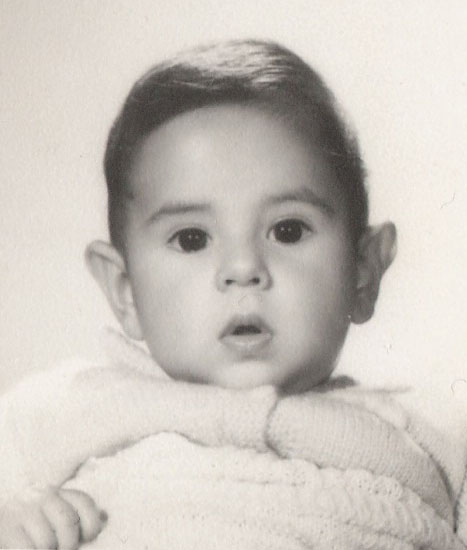

| Diego me llevaba 12 años, pero parecían más, porque siempre fue mi protector, casi como un papá en mi vida. Cuando chiquito, él me oyó llorando tarde en la noche, se dio cuenta que tenía una fiebre alta, y sin despertar a mis papas bajó a la cocina, me calentó un vaso de leche, y se sentó en mi cama hasta que me pude dormir otra vez. No había nadie mejor que él, contaba los chistes más bobos, tan bobos que me hacían reír como loco. | Diego was 12 years older than me, but it seemed more because he was always my protector, almost like a father in my life. When I was little, he heard me crying late one evening, and without waking up my parents, he went down to the kitchen, warmed a glass of milk, and sat on my bed until I was able to fall asleep again. There was no one better than him, he would tell the silliest jokes, so silly I would laugh like crazy. |

| |

| En febrero del 2008 le leí el Tarot a mi amiga Sandra. Algo muy raro apareció: teníamos que estar preparados porque alguien muy querido iba a irse muy pronto de esta tierra. En Marzo me soñé que algo malo le iba a pasar a mi hermano Darío. Inmediatamente hice la conexión y lo llamé. “Darío, lo van a matar. Le van a dar un tiro. Haga todas las vueltas para que no deje ningún papel volando. Deje todos los seguros listos.” El quedó verde. Y me hizo caso. Para mí era lógico que si iban a matar a alguien era a él, el corredor de carros y motos, el negociante de la familia que se le había escapado a la guerrilla y a los sicarios de Pablo Escobar varias veces. Cuando se enteró que iban a secuestrar a sus hijos a la salida del colegio, empacó maletas y salió del país volado. Se vino a vivir a Miami con mi mamá, que también trataron de envenenarla a finales del siglo pasado y también salió volando, dejando la casa – y a Medea, su perra chow chow – en el pasado. |

In February of 2008 I read the Tarot Cards to my friend Sandra. Something very strange appeared: we had to get ready because someone very dear to us was going to leave this earth. In March I dreamed that something very bad was going to happen to my brother Darío. I immediately made the connection and I called him: "Darío, you're going to get killed. They're going to shoot you. Have all your documents prepared. Make sure all your insurance policies are up to date." He was stupefied. And he did everything I told him. It was totally logical for me that if one of my brothers was to be killed it was him, the car racer, the business man that escaped from the guerrila and Pablo Escobar's killers several times. When he learned his sons were going to be kidnapped on their way to school, he packed everything and left the country. He came to Miami to live with my mom, who also fled the country after they tried to poison her at the end of last century. She also fled the country, leaving her house - including Medea, her chow chow dog - in the past. |

| |

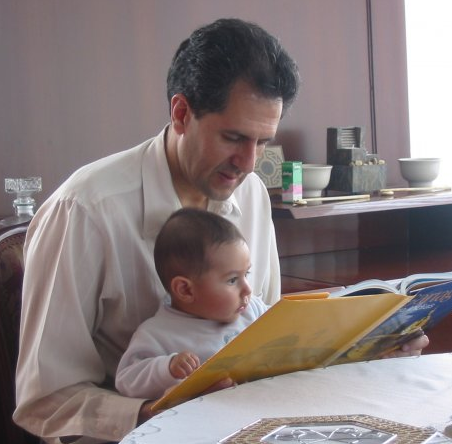

| A finales de Julio del 2008, Diego, su esposa Liliana y su bebé de un año, Julián Guillermo, vinieron de vacaciones a visitar a la abuela. Era la primera vez que mi sobrino conocía el mar. Yo me fui a pasar 10 días con ellos y a ayudar a mi mamá a organizar todo el viaje. ¡La pasamos delicioso! De verdad fue un descanso. Es la última vacación que he tenido en estos últimos cuatro años, a pesar de haber tenido muchos días libres. | Towards the end of July 2008, Diego, his wife Liliana and their one year old baby, Julián Guillermo, came to visit grandma in the US. It was the first time my nephew saw the sea. I spent ten days with them, helping my mom and driving them around. We had a great time! It was very relaxing. It was probably the last vacation I've had in these past four years, in spite of having had plenty of free days since then. |

| |

| Una tarde, mientras jugábamos todos con el bebé en la piscina, escuché un sonido extraño que venía de una palmera. El graznido de un cuervo - Maldito cuervo. En Julio, a pleno sol y en Miami. Muy raro. “Según los indígenas norteamericanos, los cuervos son los mensajeros de los muertos” le conté a Diego “ y las águilas traen las bendiciones de los dioses”. “No sabía”, me dijo Diego, y seguimos tratando de enseñarle a nadar a mi sobrino. Darío vino más tarde en muletas porque lo acababan de operar del tendón de Aquiles que se le había toteado jugando basket con los hijos. No pudo meterse a la piscina por el yeso en la pierna. |

One afternoon, when we were all playing with the baby in the pool, I heard a bizarre noise coming from a palm tree. A crow's caw - Damn crow. In July, under the sun and in Miami. Very bizarre. "According to the Native Americans, crows are the messengers of the dead" - I told Diego - " and the eagles bring the blessings of the gods." "I had no idea," Diego replied and we kept on trying to teach my nephew how to swim. Darío came a little later, walking with crutches, because he had just had surgery on his Achilles's tendon, after he tore it playing basketball with his kids. He could not get into the pool because of the cast on his leg. |

| Mi mamá no quería que se devolvieran a Colombia. Les pidió que se quedaran diez días más para que descansaran y la dejaran pasar más tiempo con su nieto. Pero Diego y Liliana tenían que regresar a sus trabajos. A Diego le pedimos varias veces que se viniera a vivir a Gringolandia con nosotros, pero él siempre se negó porque para él no existe otro país mejor que Colombia. El nunca quiso que sus hijos crecieran en un país con un sistema educativo tan malo a nivel de pregrado, y quería que tuvieran sus bases en su amada Bogotá. También soñó con que todos sus hijos se graduaran de los Andes, su verdadera Alma Mater. El pasó 9 años estudiando, viviendo y trabajando en la Mitad de la Nada, Illinois, con inviernos de Tundra y vientos del Polo Norte, y allá nacieron sus dos hijos mayores. Me acuerdo cuando me visitó en Nueva York en los noventas, salió traumatizado de un McDonald porque la empleada lo insultó, después de él ser tan buena gente. | My mom didn't want them to go back to Colombia. She begged them to stay ten days more so they would rest more and she could spend more time with her grandson. But Diego and Liliana had to go back to work. We asked Diego to come to the US and live with us here, but he always refused to leave because for him there is no better country than Colombia. He never wanted his sons to grow up in such a bad educational system, and have their roots in his beloved Bogotá. He also wanted them all to graduate from the Universidad de los Andes, his true Alma Mater. He spent 9 years studying, living and working in the Middle of Nowhere, Illinois, with tundra winters and North Pole winds. His two older kids were born there. I remember when he visited me in New York, in the nineties, he was in shock when a McDonald's employee insulted him, when he was such a nice person. |

| |

| El domingo 24 de Agosto del 2008 yo estaba preparando mi paquete de evaluación para mi promoción a profesor asociado en la Universidad de Tampa. Cuando me meto de lleno a trabajar en algo prefiero apagar mi celular para poder concentrarme. Pero ese día no lo hice. A las 5 de la tarde mi mamá me llamó:

“Santiago, tenemos que ser muy fuertes: mataron a Diego en Bogotá” ¿Cómo? ¿Por qué? No puede ser. Lo primero que se me pasó por la mente fue que lo iban a tratar de secuestrar o algo así. “Fue una bala perdida. Esta tarde a las 3. Al frente de la iglesia de Lourdes. Me acaba de llamar Liliana. Lo alcanzaron a llevar a la clínica de Marly, donde nació. Pero no pudieron hacer nada, la bala le perforó el corazón”. El piso se me cayó, empezamos a llorar. “Le conté a Darío y viene para acá con Ana María”. No fue Darío… “Un político creyó que le estaban robando el carro y salió disparando como loco. Diego estaba pasando por ahí y lo mató. El tipo se voló pero lo agarraron en la Caracas. Isabel Serpa estaba en el hospital por pura casualidad cuando llegó Liliana, y le ayudó con el bebé”. Yo me puse a caminar en el corredor de mi oficina, no había nadie ese día porque las clases empezaban el día siguiente. “Tenemos que ir a Bogotá apenas podamos”. Yo no podía ir, por mis clases. No quería ir, no tenía las fuerzas para enfrentarme a eso. Darío tenía que ir. No yo. Colgué el teléfono y llamé a Bogotá a contarle a José Luis y a Clara Inés, los empleados de confianza de la familia. Clara Inés y toda su familia empezaron a llorar, y tuve que ser yo su consuelo. Yo, el más frágil de todos. Le pedí que llamara a todas las personas que pudiera. A Diego lo adoraban, mucho y mucha gente. Pasé toda la noche en blanco terminando la última parte de mi paquete de aplicación y quemando todos los CDs necesarios. Mike, mi marido, y Larry mi exnovio vinieron a ayudarme a la universidad. Dejé todo en la oficina de la directora de carrera. Darío no pudo viajar por el yeso. Me tocó a mí. Empaqué a las carreras, y salí corriendo al aeropuerto para llegar a Fort Lauderdale. El vuelo a Bogotá salía por la tarde. Me fui en un taxi privado a encontrarme con mi mamá. Cuando la abracé me di cuenta de lo frágiles que somos, de lo pequeños que somos en estos cuerpos que al final no duran mucho. Le hice una maleta con todo lo que pensé que era necesario – como si yo supiera mucho de funerales - comimos unos huevos fritos y salimos al aeropuerto de Miami. No me acuerdo si fue Darío el que nos llevó o si nos fuimos en taxi, así de ido estaría yo. Qué ironía: un concejal de Bogotá mató a mi hermano que tanto amaba a Bogotá. Se quedó haciendo patria y la patria lo mató. Toda la familia estaba esperando a mi mamá en casa de mis tíos Jaime y Myriam, donde ella se iba a quedar. Apenas entramos al apartamento todos empezamos a llorar. La tristeza era enorme. La noche anterior al asesinato todos ellos habían celebrado los 50 años de mi prima Cristina, de Claudia - la hermana de mi tía Myriam – y de Diego en esa misma sala; las flores que les había regalado mi hermano todavía estaban frescas en el florero. Diego se despidió de todos esa noche, se fue feliz. Hasta tomó una copa de champaña – “Una no más porque me toca manejar” – y bailó delicioso. |

On Sunday, August 24th 2008, I was finishing the package for my tenure and promotion to Associate Professor at the University of Tampa. When I start working on something so important I usually turn off my cell phone so I can focus. But that afternoon, I didn't. At 5PM my mom called me: "Santiago, we have to be very strong: they killed Diego in Bogotá." How? Why? It cannot be. The first thing that crossed my mind was they tried to kidnap him or something like that. "It was a stray bullet. Today at 3PM. In front of the Lourdes Church. Liliana just called me. They managed to take him to the Marly Hospital, where he was born. But they couldn't do anything, the bullet pierced his heart." I fell to the floor. We both started to cry. "I just told Darío and he is coming here with Ana María." It wasn't Darío... "A politician thought they were stealing his car and started shooting in the middle of the street. Diego was driving by and he killed him. The guy ran away but they caught him on the Caracas Avenue. Isabel Serpa was at the hospital by pure chance when she arrived to the hospital and she helped her with the baby." I started walking back and forth in the hallway of my office, there was nobody there because classes were starting the next day. "We have to go to Bogotá as soon as we can." I could not go. I did not want to go, I didn't have the strength to face this. Darío had to go. Not me. I hung up and called Bogotá to give the news to Clara Inés and José Luis, our loyal family employees. Clara Inés and all her family started crying, and I had to comfort them, me, the weakest one of all. I asked her to call as many people as she could. Diego was loved by many, many people. I couldn't sleep that night finishing the last part and burning all the necessary CDs for my tenure package. Mike, my husband, and Larry, my ex-boyfriend came to help me at the University. I left everything in the office of the Department Chair. Darío could not fly because of his cast. It was my turn. I packed whatever I found and I ran to the airport to get to Fort Lauderdale. The flight to Bogotá was leaving in the afternoon. I caught a private limo and went to see my mom. When I hugged her I realized how fragile we are, how little we are in these bodies that at the end do not last that long. I packed her suitcase with whatever I thought was necessary for the trip - as if I knew anything about funerals - we ate some fried eggs and left to the Miami airport. I cannot remember if it was Darío who drove us there or if we took a cab, I didn't have any brains left. How ironic: a Bogotá city council member killed my brother who loved so much Bogotá. He stayed to do something for his country, and the country killed him. All the family was waiting for my mom at Jaime and Myriam's, my uncle and aunt, where she was going to stay. As soon as we entered through the door, we all started to cry. The sadness was enormous. The night before the murder, they all celebrated the 50th birthday of Cristina - my cousin - Claudia - my aunt Myriam's sister - and Diego in the same apartment; the flowers that Diego brought as a little present were still fresh in their vase. Diego said godbye to everyone that night, he left very happy. He even drank a glass of champagne - "Just one because I have to drive" - and he danced all night. |

| |

| Vi a Diego parado al lado de la chimenea, mirándonos seriamente, por una fracción de segundo. Le conté a mi tío Germán que acababa de ver al espíritu de mi hermano en la sala, me agarró de la mano, me llevó al estudio, me abrazó y empezó a sollozar en silencio.

Esa noche nadie durmió. Yo me quedé en la casa de Pasadena, abrazando a mi perrito Monzter toda la noche. El sabía que algo había pasado y no se quiso despegar de mi lado. Mi mamá no tenía la energía ni la lucidez de encargarse de nada. Me tocó todo a mi. Uno no se da cuenta de la cantidad de cosas que hay que hacer cuando alguien muere. Sobre todo en Colombia, que todo es papeleos y trámites y burocracia y colas para todo. Y plata. Una muerte le muestra a uno lo mejor y lo peor de las personas, me dijo una amiga. Y es cierto. A muchos niveles. No hay Tarot, ni premonición, ni graznido que cuente cuando esto sucede, nada lo prepara a uno para el golpe. La única metáfora que me mantuvo vivo – y todavía recuerdo – es la de un faro que representa la crisis inicial. Apenas la muerte sucede, es como si estuviéramos al frente del bombillo del faro, encandelillados, enceguecidos. A medida que pasa el tiempo, nos alejamos del potente rayo convirtiéndose en una luz que a lo lejos nos sirve de punto de referencia. Siempre va a estar ahí, pero el dolor pasa. Somos humanos. Más que eso, somos Colombianos y aguantamos lo que sea. Siempre recuerdo de manera única el abrazo que me dio mi hermano ese 1º de enero. Sobre todo cuando me dijo que estaba muy orgullo de mí y que me quería mucho. Diego tenía mucho que decir, mucho que dar y mucho por cambiar: ese es nuestro legado y nuestra responsabilidad ahora que él no está. Santiago Echeverry, Julio 2012 // Homenaje a Diego |

I saw Diego standing by the fireplace for a fraction of a second, looking at us with a serious grin. I told my uncle Germán that I had just seen the spirit of my brother in the living room. He held my hand, took me to another room, hugged me and started crying in silence. That night nobody slept. I stayed in my family house, hugging my little dog, Monzter, all the time. He knew something was wrong and never left my side. My mom did not have the energy nor the the lucidity to take care of anything. I had to do it. You never realize the amount of things you have to do when someone dies. Especially in Colombia, where everything is paperwork and errands and bureaucracy and lines all the time. And money. Death shows you the best and the worst in people, a friend of mine told me. And it is true. At several levels. There are no Tarot Cards, nor premonitions or caws that matter when this happens. Nothing can prepare you for the shock. The only metaphor that kept me alive - and I still remember - is the one of a light house that represents the initial crisis. When death happens it's as if we were standing right in front of the bulb of the light house, stunned, blinded. With the passing of time, we get farther away from the powerful beam and it becomes just a light in the distance that acts as a landmark for our lives. It is always going to be there, but the pain goes away. We are human. More than that, we are Colombian and we can stand anything. I always remember dearly the hug my brother gave me that new year's eve, especially when he told me he was very proud of me and that he loved me a bunch. Diego had a lot to say, a lot to give and a lot to change: this is our legacy and our responsibility now that he is not here. Santiago Echeverry, July 2012 // A tribute to Diego |

| |